A sermon preached by the Dean of Melbourne at Choral Evensong on the Feast of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple 2024:

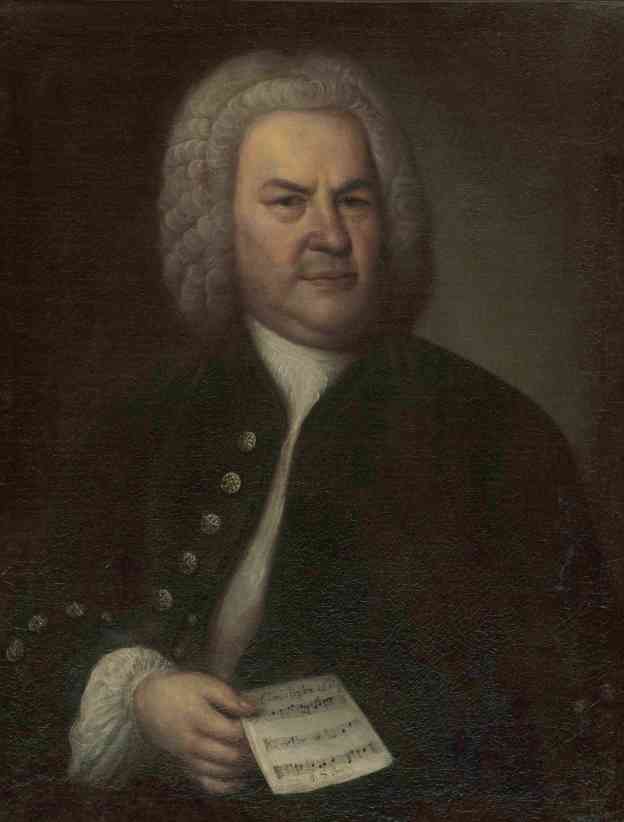

Tonight’s readings for the celebration of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (1 Samuel 1.21-28 and John 2.13-25) take us away from the infant Jesus in the arms of aged Simeon (shown above in our stained glass windows), when he sang his prophetic song about how he would enlighten the nations, and become the glory of God’s chosen people, Israel. In our second lesson, from John’s gospel, Jesus is not brought up to Jerusalem for purification to the Temple. Instead, he purifies the Temple. In John’s story, we meet Jesus as an adult—baptised by John in the Jordan, he had been proclaimed by John the Baptist to be ‘God’s Son’ and the ‘Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world’. He had gathered disciples around him, who had also proclaimed him to be God’s Son, and the King of Israel. In turn, he promised them that they would see ‘heaven open and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man’. And he had just attended a wedding in Cana of Galilee, and used six giant water jars for purifying household objects according to the Jewish law to make 800 litres of the finest wine.

A few days after this, his first miracle, or sign, changing objects for ritual purification into vessels for divine generosity, Jesus goes to the heart of ritual worship in Jerusalem, and symbolically purifies the Temple. Jesus and his disciples had gone up from Galilee in order to join with countless other pilgrims in celebrating the Passover; the liberation of his people from slavery in Egypt. As Jesus entered the temple, he found it not to be a place of prayer. Instead, it was busy with people selling cattle and doves, and exchanging Roman money for Temple money. Jesus, we read, ‘making a whip of cords, and drove all out of the Temple’, thus purifying the place of ritual sacrifice (Jn. 2.15). His action caused wide-spread confusion: bawling animals running about aimlessly; money changers scrambling for their coins on the floor of the temple courts; officials trying to take hold of Jesus, shouting at him, and arguing with him about the rights of his case.

John places the cleansing of the Temple right at the beginning of his story of Jesus’ public ministry. The other three evangelists tell this story at the end of their gospels, just before Jesus’ arrest, trial an crucifixion. But for John, this story is a continuation of Jesus’ first sign, which signalled the purification of the whole world at the time of fulfilment: the use of the jars of water for purification under the Jewish law for the new wine of the Kingdom of God mirrors the shedding of his blood on the cross to make pure the world from sin and evil. And now he is taking that new wine, to the heart of Jewish ritual life by purifying the Temple, and points again to the cross where he will break down the final barriers in human living—by conquering death and making peace with God. And where in the story of the wedding at Cana, no one other than Mary, his mother, the disciples, and the wedding guests witnessed his re-purposing of things set aside for the observance of the ritual law for the new things God was doing; here, in the Temple, everyone witnessed his actions, and found them to be outrageous.

Because Jesus not only drove out the salespeople, but also held the officials to account for their actions: ‘Take these things out of here!’, he told them, ‘stop making my Father’s house a marketplace’ (Jn 2.16). Jesus’ friends have already proclaimed him to be God’s Son, and they interpret his actions from that vantage point: ‘Zeal for your house will consume me’, they recall the scriptures—they know Jesus to be God’s Son, and of course, God’s Son would show zealous anger about his Father’s house. But the people gathered in the Temple have only just met Jesus. They have no idea of who he is, and why he is doing what he is doing. And that the place where they are meeting is not their Temple, but ‘my Father’s house’. In fact, it is not even a Temple, but a marketplace. In this brief interchange, Jesus shares with them incredible, and potentially offensive news: that he is God’s Son, and that God is displeased with their worship. And the people are startled and angry, and demand to see the authority for his actions. ‘What sign can you show us for doing this?’, they ask him. ‘What miracle will you perform to show that you truly are acting with the power of God?’

But we, who have read John’s story carefully and understood it from the vantage point of the cross, know that Jesus has already performed his sign. Miles away, in Cana at Galilee, when he turned the jars of ritual purification into a giant wine cellar and so signalled an end to religious rites that are without meaning. Instead of performing another sign, he makes the people a promise instead: ‘Destroy this temple’, he tells them, ‘and I will raise it in three days’ (Jn 2.19). John tells us that his listeners thought that Jesus was speaking of the building that surrounded them: Herod’s Temple, a grandiose shell that had been in construction for forty-six years already, and would still remain incomplete for another thirty years. But the evangelist tells us that Jesus was speaking of another Sanctuary. Not the physical structure of Herod’s incomplete house of prayer, but the ‘Temple of his body’.

The raising of Jesus on the cross—the destruction of his own body—and the raising, three days later, from the tomb would be the sign of God’s authority. ‘The real temple of God’, Jesus tells his listeners, ‘is not Herod’s building site in which we stand, but he stands among you right now. ‘The complete offering for the forgiveness of sins’, he adds, ‘can never be made by killing a newly purchased bull on the splendid bronze altar of this temple, but only by the sacrifice of God’s own Son on a cross’. A scapegoat sent to die in the desert once a year can never provide a sacrifice powerful enough to break the power of sin and evil and the barrier between God and man, once and for all. Only the ignominious death of Jesus on the cross can tear apart the curtain that separated the Holy of Holies from the world; can throw wide open the sanctuary of God in the Temple (Mk. 15.38par).

As the letter to the Hebrews explains: ‘It is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins. Indeed, when Christ came into the world, he said, ‘Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired, but a body you have prepared for me; in burnt offerings and sin offerings you have taken no pleasure. Then I said, “‘”See, God, I have come to do your will, O God”. … Christ abolishes the first in order to establish the second. And it is by God’s will that we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all’. (Hebrews 10.5-10)

When they look at the world from the vantage point of Christ’s resurrection, the disciples know how to make sense of Jesus’ words, and the Scripture that promised the hope of new life brought by the death of the Messiah. That the sacrifice of Christ on the cross remains valid for all times and in all places; that that sacrifice has been accomplished once for all generations when Christ gave his own body as a Sanctuary and sacrifice for God as he breathed his last on the cross, purified the world from sin and death, and ‘abolished the first in order to establish the second’.

And as he prophesied at the beginning of John’s story, three days later, the Temple of his body was raised again. When Jesus died, the Temple of his body was destroyed, abolished. When he rose from the dead, that bodily Temple was renewed. This new Temple is there for all generations: not just there to be seen by the first disciples of Jesus at the empty tomb, or to be touched by the doubting Thomas. No, this new temple stands today wherever people want to become the ‘living stones’ that make up God’s sanctuary on earth. For in the light of the cross and resurrection, the God who once could only ever be encountered in the Holy of Holies of the Jerusalem Temple has come to dwell right among us. Not only in the risen body of Jesus, but in our own bodies; calling all of us to become living Temples of his Holy Spirit.

Just as he had prophesied in our second reading, on the first Easter day the Temple of Christ’s body had been raised up triumphantly. It remains with us today as a sign of God’s victory over sin and death. But it isn’t just a testimony to God’s work of resurrection, accomplished some two millennia ago. Rather, it is a constant invitation. A call to each of us to let ourselves be built into living Temples—to become ourselves homes of God’s Holy Spirit—to be the places where God may dwell on earth (1 Pet 2.5). A call to be purified as Christ is pure, and to become people who through their faith, and through their actions reflect the greatest of all of Jesus’ signs, the sign of lives restored and transformed forever to his glory.

Now to him who by the power at work within us is able to accomplish abundantly far more than all we can ask or imagine, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus to all generations, forever and ever. Amen.

Image: Mary and Joseph present the infant Christ to Simeon, Stained Glass Window at St Paul’s Cathedral Melbourne.